|

1966

COMBAT CRUISE

After another training cycle and a considerable personnel turnover, VA-152

again deployed aboard U6S ORISKANY with CVW-16. The ship left San Diego on 29 May and, after stops in Yokosuka, Japan and

Cubi Point Philippines, arrived on Dixie Station on 30 June. In the eight day period following, the squadron flew 128

sorties against Viet Cong troop concentrations, buildings and supply caches. During the night of the 7th ORISKANY moved

north and launched missions from Yankee Station late in the next morning.

On 11 July a four

plane Special RESCAP composed of CDR Smith, LCDR Smith,LCDR Schade and LT Feldhaus picked up LTJG Adams of VF-162 near the

east-west ridge north of Haiphong. The rescue was deeper into the North-east Triangle than any which had preceded it.

(From

the book "VA-152, A SPAD SQUADRON IN VIETNAM", a history of VA-152 during the time the squadron served in

Vietnam aboard the USS Oriskany in 1965, 1966 and 1967. This history was written by LT J.M. (Bud) Watson

in December of 1967. )

|

|

LT John A. (Jack) Feldhaus had been on Dixie Station off

South Vietnam for 8 days and had flown several missions into South Vietnam when the USS Oriskany moved north to Yankee Station

off North Vietnam and began launching missions into North Vietnam on July 8.

Three days later, Jack was involved in his first

rescue effort of a downed Navy airman. He was one of four pilots launched on July 13 on a mission to travel further

north into Vietnam than any other attempted rescue. As his commanding officer and his wingman flew above, Jack as wingman

of LCDR Eric Shade, accompanied the helicopter to the downed pilot, LTJG Rick Adams, and fought off attacking forces and avoided

AAA while guiding the helicopter out of the country. I've pulled together four

different accounts of this rescue below. As usual, everyone knew who the downed pilot or pilots were and the personnel

of the rescue helicopter, but seldom were the names of the pilots known who provided the firepower and cover for the rescue

to take place.

|

|

|

|

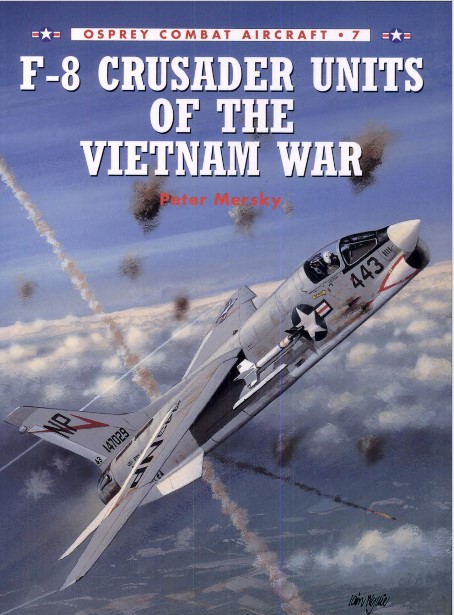

LT (jg) Rick Adams story from the F-8 Crusader book

|

|

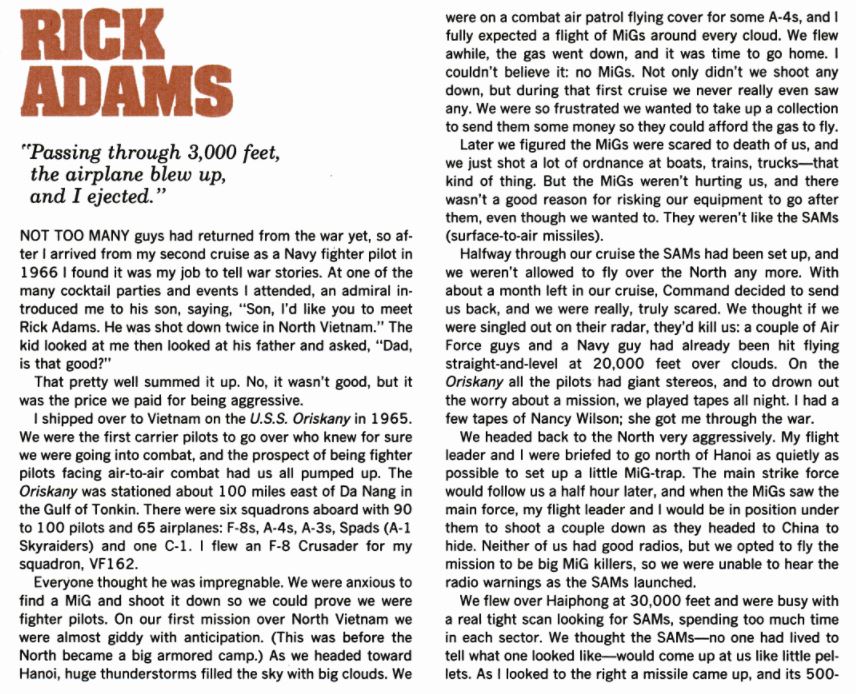

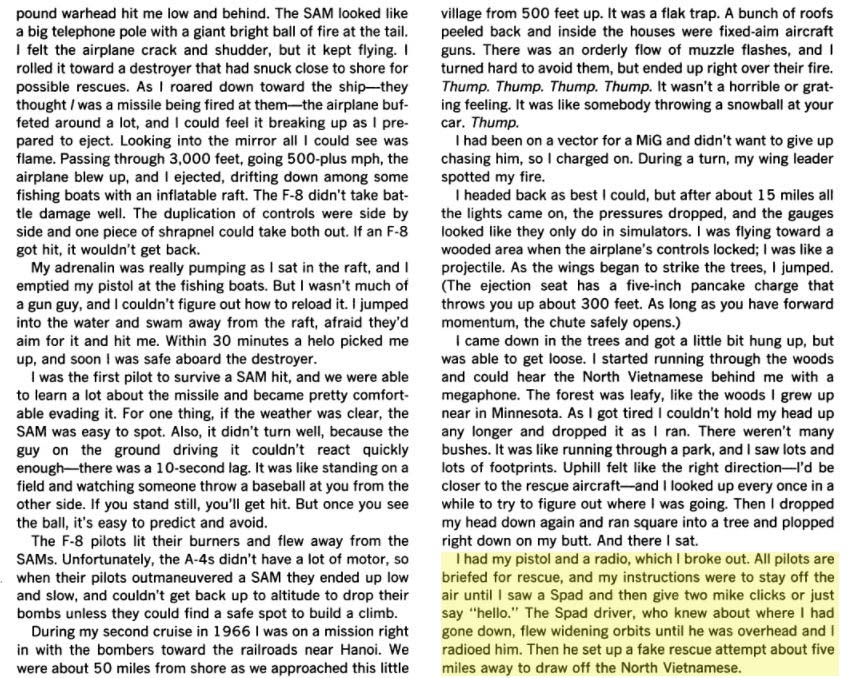

LTJG Rick Adams returns from being rescued.

LTJG

Rick Adams returns from being rescued after being shot down on 5 October 1965.

He is greeted by his squadron mates, including his skipper, Cdr Dick Bellinger,

who hold replicas of the SA-2 SAM that got him. Lt Cdr Butch Verich holds a

model of a gun-prophetic, because ten months later Adams would again be shot

down, this time by communist ground fire, on 12 July 1966.

|

Rick Adams, a native of Minneapolis, Minnesota, enjoyed his

place as wingman

for Cdr Dick Bellinger, the unit's X0 who then became its CO. 'Belly One', as

he was affectionately called,

could he rough as a cob, but he and Adams seemed to mesh as a team. On 5

October 1965, Adams and the skipper were hunting SAMs and they found them.

'Bulb', Bellinger called, ‘get the hell out of here’. Referring

to Adams' prematurely receding hairline,

he was trying to warn his wingman of an on-coming missile that had just

launched and seemed to be heading for Adams' F-8 (BuNo 150848 AH 227).

Unfortunately, Adams' radio had gone out and he didn't

hear Bellinger's call. He did see a flash as the missile flew past his aircraft

just before exploding. Adams made a hard, right turn, pointing toward the South

China Sea. He was lucky at least in one respect —

if the SAM's 500-lb warhead had detonated any closer, it would have destroyed

the F-8, giving him no chance to escape the blazing inferno that was now devouring

the struggling fighter.

While Bellinger kept

calling his number two, pleading with him to eject, Adams doggedly headed for

the water. Like most American crews, he

did not want to punch out over land, where he would probably be captured. The

young pilot remembered having passed some destroyers on the way in, and now he

hoped he could find them before ejecting.

Finally, the

Crusader gave up the ghost and exploded.

Adams ejected through the fireball, and he somersaulted through the air still

attached to his seat. After a few seconds, the small drogue 'chute opened, then

the larger, primary 'chute followed. Adams separated from his seat and began

the descent toward the water. As he hit the sea, Adams released his harness and

raft. Paddling over to his one-man raft,

he looked up. 'Belly One' flew by

waggling his wings in encouragement. He

was so low that Adams could see into his skipper's cockpit!

The downed pilot

hauled himself into the raft and began sorting out his situation, arranging his

survival gear around him in the small, rubber, container. By now, Bellinger

had alerted the rescue

forces and was circling over Adams for the incoming helicopters. He was also

worried about any enemy attempt to retrieve the downed aviator.

When a helo arrived,

Adams rolled out of his raft into the water. However, he hadn't noticed how

badly his hands were burned. Immersing them in the salt water made him cry out

in surprised pain. The swimmer from the helicopter jumped in to help Adams get

into the rescue sling, and before long the bedraggled aviator was on

board the cruiser USS Galveston (CLG-3), where he received a preliminary

examination and first aid for his burns. Returning to Oriskany the next day,

Adams was

greeted by his squadron-mates, who formed a gauntlet, complete with models of SAMs

and flak guns. ‘Belly One', meanwhile, smacked his wing an on the rear with a

paper missile.

'How's it feel

to be a hero, ‘Bulb' one of his friends

asked. It was a facetious question. but

Rick Adams was glad to be around to hear it.

Four months

later, Rick Adams flew a mission that gained

him the Distinguished Flying Cross. Again, he was dicing with SAMs, a battery

of

eight rocketing toward his flight, but he maintained his station through the

intense defenses. But the enemy was not

through with him.

By July

1966, Adams was on his second tour with VF-162,

one of only half a dozen members of the 1965 cruise to go on the second combat

deployment. On 12 July he launched on a TARCAP mission in F-8E 150902 (AH 203),

his target that day being near Haiphong, one of the most heavily defended areas

in the north.

When his Crusader was

apparently hit by small-arms fire, Adams faced another ejection. Fire spread

from the tail to the forward fuselage as the F8 rolled to the right.

`See you in a year',

Adams called — he'd meant to say, 'ten years' — and he punched out at 2500 ft

and 400 knots. As his Crusader plunged into a mountain. he landed near a

village. Now, he was involved in a classic escape-and-evasion run for his life.

The 'bad guys' were already looking for him, and he could hear them. He also

knew that his friends had already called for the search-and-rescue (SAR)

forces, and the helicopter was probably inbound. It was a question of who got

to him first.

Four Skyraiders

arrived escorting the H-3 helo, trying to keep the 'chopper' clear of enemy

fire coming from all directions. The helo crew spotted Adams in the underbrush

and sent the sling down for him. Strapping

himself in, the F-8 pilot 'rode' the sling up through the trees, finally

tumbling into the shuddering H-3 as more groundfire reached out.

As the two enlisted

crewmen manned their machine guns, the battered, but thrilled Adams stared

through a cabin window as the helo turned for home, escorted again by the

protecting `Spads', whose pilots fired their remaining ordnance at the gun

positions on the ground.

Lt Bill Waechter, the

H-3 co-pilot, was on his first mission into North Vietnam. 'Is it always this

rough?', he asked Adams, unaware that this had been his passenger's second rescue

in eight months.

`Seldom as

rough as this', Adams replied, perhaps

tongue-in-cheek. Four hours after launching from Oriskany, a bedraggled

Rick Adams was back on board, to be greeted once more by a line-up of squadron pilots.

'No one gets shot down twice', they hooted. They were wrong.

Rick Adams'

second shoot down elicited a full-page

article in Time magazine for 29 July 1966. Determined by the Navy to be 'combat

limited', Adams was sent home. He flew with the Blue Angels in 1968 and

eventually retired as a Commander in 1982.

LT (jg) Rick Adams story from a 1966 Time Magazine article

After surviving being shot down and rescued the previous October, Lt(jg) Rick Adams had become something of a lucky charm

amongst the pilots of VF-162 due to the tale of his cool demeanor under extreme duress. On this strike, Adams was flying the

TARCAP to protect the main strike force from MiGs. Multiple SAM warnings had forced the strike package to evade, trading precious

altitude in the process. Eventually the flight ended up low enough to be in small arms range. Flying low, Adams took hits

in his tailpipe which quickly caught fire.

Once again Adams turned his burning Crusader for the safety of the gulf. He cleared one ridge line before the Crusader began

an uncontrollable death roll to the right. Adams’ wingman on this flight was Lt Cdr Butch Verich, who began calling

on the radio for Adams to eject. A terse exchange followed with Adams finally commenting, cool as ice, “Sorry about

that. See you next year!” before he ejected.i He had really meant to say, “See you in ten years.” Adams

landed in rugged jungle near a village, less than twenty miles from Hanoi and the plethora of defenses surrounding the city.

Any rescue attempt was certain to be hotly contested.

Fortunately, Lt Cdr Verich followed Adams’ chute and marked his location, thus giving the CSAR forces the information

they needed to attempt a rescue so far inland.ii A flight of four VA-152 Skyraiders orbited nearby as the RESCAP. Cdr Gordon

Homer Smith, VA-152’s Commanding Officer left two Skyraiders with the rescue helicopter, while he and his wingman flew

ahead to begin the rescue. Lt Cdr Verich and Lt Dick Wyman talked the Skyraiders onto Adams’ parachute, which was hanging

from a tree. Cdr Smith assumed on-scene command of the rescue and called for the CSAR helicopter, a Sea King from HS-6, to

proceed to Adams’ location. Smith began coordinating the replacement of the fuel limited jets orbiting overhead, while

his wingman reported areas of enemy fire. At the higher altitude, Smith’s wingman acted as a communications relay to

the inbound rescue forces.

Lt Cdr Eric Schade and his wingman, Lt Jack Feldhaus, escorted the helicopter towards Adams.

The pair avoided areas of heavy ground fire where possible, though they made repeated runs on several gun positions in order

to draw fire away from the helicopter. Despite hits to Schade’s Skyraider, they suppressed 37-mm. AAA fire long enough

for Lt Bill Waechter’s Sea King to reach Adams. While the helicopter hovered overhead its crew lowered a jungle penetrator,

(essentially a heavy weight with folding seats capable of being lowered through the dense jungle foliage) and pulled Adams

to safety. As Adams arrived in the cabin of the SH-3, ground fire erupted.

Lt Waechter was on his first mission over North Vietnam. “Is it always this rough?” he asked, not knowing that

this was Adams’ second shoot down in less than nine months.

Less than four hours later, Adams was back aboard the Oriskany. The rest of the strike landed much earlier and they all crowded

around him to welcome him home. Fellow squadron members, each carrying mock missiles and guns lined up around him as he walked

their gauntlet. “No one gets shot down twice,” they hollered. As the war ground on, they would be proven wrong

on more than one occasion.

Adams mused over the events, “The carrier isn’t much, but it beats being paraded around Hanoi with a rope around

your neck.”

The navy declared that after ejecting twice, Adams could not fly over North Vietnam anymore. He was transferred back to the

U.S. where he became a member of the navy’s aerial demonstration team, The Blue Angels.

LT (jg) Rick Adams story from the book "Leave No Man Behind" by George Galdorisi

and Thomas Phillips

Five days after that

"routine" unopposed rescue, on July 12, 1966, it was a little

different. A Crusader pilot from VF-162, Lt (jg) Rick "Bulb" Adams's

and his mates were taunting the MiG pilots at Kep airfield by taking turns

doing touch and gos on the airfield runway, trying to get the MIGs to take off

and fight. The MIGs did not take the challenge, but the indignant airfield

defenders bagged Adams, who was forced to eject right off the end of the runway

into dense, jungle-covered low hills. He was seventy miles inland, and about

thirty miles north-east of Hanoi itself. All available navy aircraft quickly

diverted

to the scene in a silent, mutual understanding that one with such chutzpah

needed saving.

The HS-6 Big Mother

orbiting North SAR, flown by Lt. Bill Waechter and Ltjg Bob Wildman, was

cleared to attempt a rescue: a bold decision so close to Hanoi and a major MIG base.

Picked up by four VA-152

A- ls, call sign Locket (My note: Locket

flight made up of the VA-152 CO CDR Gordon

Smith and his wingman CDR J. S. Smith along with LCDR Eric Shade and his wingman, my brother,

LT John “Jack” Feldhaus), the Big Mother coasted in northeast of Haiphong,

passing over the islands at 2,500 feet, high enough to avoid accurate small

arms, but they were immediately taken under heavy fire from a variety of

large-caliber AA guns. Ugly black clouds of 100mm flak quickly began to burst

at the helicopter's altitude and walk toward them, then

stopped getting closer, and then moved away. (A post-mission debrief credited

effective electronic warfare aircraft with confusing the radar-controlled guns.)

The fire followed

them inland, and Waechter gave ADJ2 Harley Olsen and AX3 Michael Brantley permission

to fire back at any enemy they could see. Both cheerfully began to return fire toward

every source of tracers they could see near their flight path. At one point,

Waechter zigged right toward an AA gun. Olsen, spotting the gun pit, dispersed

the gunners with a well-placed stream of fire, just as they inadvertently flew

over it, the big helicopter disappearing from the gunners' view before they

could re-man the gun.

Locket leader LTCDR Eric Shade broadcast, “They’re

hosing

the helo”. Great, thought Wildman.

Finally, the four Lockets escorting Big Mother led her to

the vicinity of the downed pilot, in the densely forested area. Not far away,

jets swirled around the airfield, attacking anything that moved and pulling

hostile fire from the low-level helicopter. Even though Wildman achieved voice

communications with the downed Adams, the Big Mother crew could not spot him,

and he could not see them.

Luckily, someone

sighted a parachute in the canopy tops down in a forested gorge, and from that

clue, they caught a glimpse of Adams through the trees. Having only one hundred

feet of cable on the Navy hoist, Waechter and Wildman had to make a

near-vertical descent into the close confines of the gorge to enable the hook

to reach the ground. With Brantley and Olsen clearing the tail rotor and rotor

blade tips from the surrounding treetops, Waechter eased carefully down into

the gorge.

The surrounding

heights cut off all wind, and the heat of the July day compounded the weight of

the armored helicopter to require more power than the engines could deliver.

When Waechter applied up-collective to increase rotor-blade pitch and arrest

the descent, the engines went to full power trying to keep the rotor rpm at the

desired 100 percent. Full power on both engines still could not do it, and the

rotor rpm began to droop as Waechter continued to raise

the collective lever

to keep altitude. He had no choice if he wanted to avoid settling disastrously into

the trees for lack of lift.

As the main rotors

slowed, the tail rotor likewise began to lose rpm, being mechanically connected

to the main rotors through the transmission. As the tail rotor rpm slowed,

there was no longer enough tail-rotor power to hold the helicopter's desired

head-ing. Slowly, the nose began to rotate to the right. Waechter had the left

tail rotor control pedal shoved all the way forward to stop the rightward

rotation of the nose, to no avail.

Olsen, noting the

right turn as he lowered the jungle penetrator through the trees to Adams, called

for the pilot to stop the turn. "Can't," came the terse reply.

Around they went,

slowly turning 180 degrees in about one minute. Olsen went back to

concentrating on getting Bulb Adams on the hoist and bringing him up without

getting entangled in the trees.

With Adams on the way

up, Waechter eased off his extreme left rudder and rocked slightly right,

dipping the nose ever so slightly. The combination of control inputs

accelerated the slow turn, which eased the power demand on the tail rotor, and

made an ever so slight amount of power from the tail rotor available for the

main rotors, allowing the helicopter to begin to climb. Gingerly lifting

vertically while spinning to the right, the Big Mother rose out of the

claustrophobic

confines of the gorge, drooping rotor rpm to the lower limit of controllability

as they elevated. Once clear of the hole, they nosed over and picked up ground

speed as they turned, providing a bit more rpm for the main rotors.

Finally away from the

gorge, the rotor rpm rose back to normal as the speed increased. They had

pulled off the near-impossible pickup by unparalleled airmanship: the most

exquisite of subtle control movements. The navy men cleared the gorge and

headed for the safety of the sea. As they came out of the mountain area, the

enemy AAA picked up where it had left off and threw up repeated salvos all the way

back to the coast.

The Big Mother

accelerated beyond one hundred knots, impatient to escape with their prize, and

the airframe began to vibrate and shake like a hound dog passing a peach pit, a

side effect of the added armor location and weight known to the helicopter crewmen,

but not to Bulb Adams, Crusader pilot. Home the crusader came from the hill

and the

sailors, home to the sea.

LT (jg) Rick Adams story from the 2011 HS-6

Reunion in Corpus Christi Texas

Following is a report from the 2011 Raunchy Redskin’s

reunion in Corpus

Christi.

HS-6 Rescue Symposium - noted Combat SAR authority and author

Tom Phillips conducted a half-day seminar on CSAR operations during the Viet Nam war to provide our loved ones with a better

understanding of just what we did during those long deployments. He also moderated a discussion about the rescues of Rick

Adams and Tiff Hawks by HS-6 crews.

Bill Waechter was the pilot, who along with his crew, received

the radio message that Rick Adams plane had been shot down in enemy territory and needed rescuing…ASAP…if not

sooner.

Rick Adams, listens as Bill Waechter relays his perspective of rescuing

him

Rick Adams stayed in the Navy and went on to become

a Blue Angel.

LT (jg) Rick Adams story In his own words

Awards resulting from the rescue of LTJG Rick Adams.

SYNOPSIS OF THE EVENTS PRECIPITATING THE FOLLOWING AWARDS

LT W. WAECHTER SILVER STAR MEDAL

LTJG R. A. WILWAN DISTINGUISHED FLYING CROSS

ADJ2 H. R. OLSEN AIR MEDAL

AXJ M. D. BRANTLY AIR MEDAL

The Helicopter and crew during a mission to attempt to locate and rescue a downed

pilot were vectored deeply into the enemy territory of North Vietnam. The crew, subjected

to heavy and intense antiaircraft and automatic weapons fire while approaching enemy territory, skillfully employed evasive

measures and succeeded in flying inland over seventy miles of heavily defended territory to reach the rescue site in a mountainous

area. After the downed airman established communication with the rescue helicopter over

his survival radio and described his precarious position, the crew determined to effect a rescue, hovered over the gorge and

began the treacherous vertical descent to the position where the survivor was thought to be. Expertly

maneuvering the helicopter into a ragged hover by sacrificing directional control and varying the pitch in the rotor to maintain

speed and lift, the crew succeeded in rescuing the downed pilot after locating the airman under dense foliage and lowering

the rescue sling. Reaching the safety of the open sea after running the gamut of a tremendous

barrage of antiaircraft fire, the crew displayed outstanding courage and airmanship throughout, thereby upholding the highest

traditions of the United States Naval Service.

|