|

Martha Ann "Nannie" Haskins

|

|

Born: 24 May 1846 in Clarksville, TN

Died: 22 Feb 1930 Greenleaf, Graysville, KY

Married: Henry Philips Williams

6 Oct 1870

Trinity Episcopal Church

Clarksville, TN

Nannie is the second wife of Henry Philips Williams.

|

Children of Henry Philips Williams and Martha

Ann "Nannie" Haskins

Edward Haskins Williams married Berta "Bert" West

and produced Henry Philips who died as an infant and Emily West. (his descendants live in Alabama)

Ben Philips Williams married Cora Blackwell and produced Eleanor Branch Williams.

He then married Marion Bakerand produced Adrian, Nancy Haskins Baker, and Ron. (descendants live in MO)

John Frederick Williams (Gerri's husband's grandfather) married Anne Nottingham

"Nan" McKown and produced Nick Van Boddie Williams, Henry Philips Williams and John Frederick Williams. The last two had no

children.

Teressa "Tress" Stark Williams married Dr. Newman Ross Donnell and produced

Jess Franklin Donnel, Newman "Ned" Ross Donnell, and Ben Philips Donnell.? (descendants in MO and Washington DC)

Robert James Williams married Orena Roselle "Rena" Dryer and produced Robert

James II, diane, and Haskins. (Descendants in Birmingham, AL)

Lucille "Lucy" Stark Williams lived to 86 (never married)

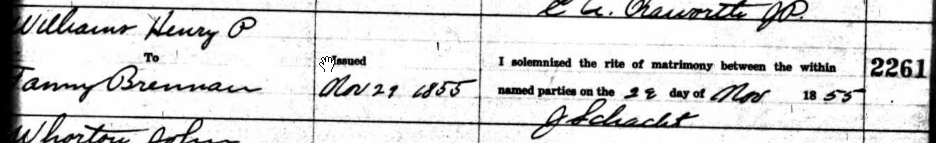

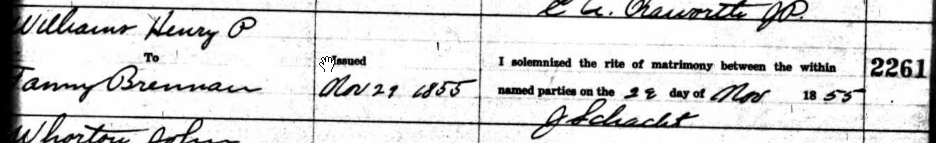

Henry Philips Williams married his first wife, Frances Brennan, 29 November 1855 in Nashville, Davidson Co., TN. She was

born in November, 1834 in Tuam, Ireland and died 27 June 1869 at her home, Greenleaf, Graysville, Todd Co., KY.

Children of the first wife of Henry Philips Williams, Frances Brennan.

Thomas Brennan Williams, died at 11 years old

Rowena Ewing Williams, married Charles Morris Day II and produced five children:

Mary Frances

Henry Philips

Rowena "Ruggles"

Charles Morris III

Harry Williams Day (died as infant) (named after uncle)

Marguaretta or Gretta Kendall Williams (never married)

Harry Lee Williams, married Virginia "Vivy" Vance Nicholas and produced two

children:

Carter Virginia

Rowena Hickman

Frances "Fannie" Victorine Williams (died as infant)

Frances Brennan Williams, the last child and daughter of Frances Brennan and Henry

Philips Williams

Frances Brennan Williams married Nicholas Van Boddie and later married Allan Sanford.

She is buried with Nicholas Van Boddie in Waco, TX along with her daughter, Frances

Van Boddie who married William Topping Merry. Nicholas Van Boddie was the son of Willie Perry

Boddie and Martha Rivers McNeill.

Nannie Haskins raised France's children as if they were her own.

Nannie is best known for the personal diaries she kept from the time she was a small child living on the Cumberland River

before and during the Civil War. She continued to keep a diary off and on for the rest of her life.

Nannie is a distant relative of her husband Henry. Their relationship can be seen in the below partial family tree.

Benjamin Philips and his wife had five children, one of whom is Anne Philips, born in Nashville TN in 1796. Anne

married John S. Williamson in Nashville TN on 22 Aug 1816. This union produced two children, Tennessee Stark Williamson,

a daughter who was born in 1817, and a son, Benjamin Franklin Williamson (1819 - 1896).

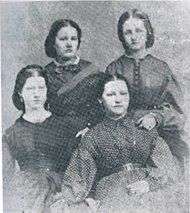

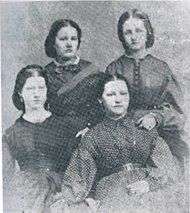

Tennessee Stark Williamson married Dr. Edward Branch Haskins on 24 Dec 1840 in Todd County KY. They had four children

as seen in this picture that was taken after the death of the youngest child,Tennessee also known as Tennie, who

is lying in her mother's lap.

Benjamin A. Haskins, 1841 - 1912

Robert James Haskins, 1844 - 1862

"Nannie" Martha Ann Haskins, 1846 - 1930

Tennessee Haskins, 1847 - 1850

| Surname: |

Tennessee Haskins |

| Year: |

1850 |

| County: |

Davidson CO. |

| State: |

TN |

| Age: |

3 |

| Gender: |

F (Female) |

| Month of Death: |

Oct |

| State of Birth: |

TN |

| ID#: |

MRT197_140616 |

| Occupation: |

NONE LISTED | |

|

|

|

|

Nannie Haskins on lower left with school friends from Clarksville Female Academy. One is Hattie Donoho and one

is Janie Moore.

|

|

Nannie Haskins with her youngest daughter Lucy Stark Williams.

|

|

The above picture was taken at the home of Nicholas Boddie somewhere near Guthrie KY. Nicholas is the husband of

the youngest daughter of Frances Brenan and Henry Philips Philips.

Henry Philips Williams is sitting just to the right of the center porch post, holding the child Charles Morris Day III.

Nannie Haskins Williams is standing behind Henry just to his right.

Nannie's mother, Tennessee Stark Williamson is sitting in the second row to the left with the black shawl on her head.

Sitting beside Tennesse is her son and bother of Nannie, Benjamin Haskins.

Go to the Henry Philips Williams web page to see more pictures of Nannie's family and Greenleaf where she lived with Henry.

The Nannie Diaries

By MINOA UFFELMAN

It was February 16, 1862, and Nannie Haskins, a 16-year-old native of Clarksville,

Tenn., was anxiously awaiting news of the Battle of Fort Donelson, just a few dozen miles downriver. Like her neighbors, Nannie

knew that if Fort Donelson, which guarded the Cumberland near the Tennessee-Kentucky border, and Fort Henry, which did the

same along the nearby Tennessee River, were to fall, the entire Confederacy would suddenly be at grave risk. It was even more

personal for Nannie: her brother Robert was serving at Donelson.

Nannie later wrote of the chaos that ensued that night, after news of the Confederate defeat arrived

atop a wave of soldiers and civilians fleeing the victorious army of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant: “It was Sunday the news

came such panic-stricken people were never seen before. The wounded were being brought up. They were to be attended too —

a great many died on their way up here, who were buried. The citizens were running. There were already two hospitals here

which were filled with the sick.” One makeshift hospital was so near the Haskins home that Nannie heard moans of the

wounded throughout the night.

Grant’s troops soon captured Clarksville, and soon after Nashville, less than 50 miles away.

For the rest of the war it remained occupied by federal troops, and Nannie’s diary gives us a unique insight into Clarksville’s

daily life. Her entries mix information about battles, wounded neighbors, guerrilla warfare and violence along with descriptions

of domestic life, school assignments, social events and scores of local people struggling to maintain their lives as best

they could in the midst of Civil War.

The Haskinses were a prosperous family and prominent in the Clarksville community. Edward Branch

Haskins, a physician, and his wife, Tennessee Stark Haskins, owned several slaves before the war and were well connected with

the professional and political classes of the region. Nannie, a bright and curious girl, received an excellent education at

Clarksville Female Academy; she loved literature, studied French, sang, played the piano and even took guitar lessons.

In other words, she was a well-spoken witness at the heart of the early Civil

War in the west. Clarksville, a city of about 5,000 people in 1860, is situated at the confluence of the Cumberland and Red

Rivers, northwest of Nashville; river and rail transportation made it a regional commercial center for local tobacco and iron,

as well as numerous slaughterhouses. Like much of the Upper South, its townspeople did not support secession until after the

firing on Fort Sumter. Afterward, however, it became a central part of the Southern war effort, serving as a Confederate recruiting

center. Both Nannie’s brothers, Robert and Ben, enlisted.

The loss of Clarksville, along with the rest of West and Middle Tennessee, was calamitous for the

Confederacy, and the Haskins family as well. Robert was taken prisoner at Fort Donelson and transferred to a Northern prisoner

of war camp. Nannie wrote: “My dear brother was among the number who was to be sent and incarcerated in a northern bastille

where he languished and died.”

After the defeat, Clarksville braced itself for the unknown. Looting was an immediate concern, while

violence continued for the duration of the war. After a warehouse of army rations was left open, recalled one resident, “The

rabble, white and black, from all parts of town were not slow in availing themselves of its contents.” Union guerrillas

looted private property and slaves. Another young Clarksvillian, Serepta Jordan wrote, “What may we poor Rebels in this

part of Lincolndom expect? we are left entirely to the mercy of vandals.” To this lament, she added, “losing 50

or 100 negroes was the most maddening.”

In March, Federal troops vandalized local Stewart College, stripping it bare of books and scientific

equipment. Nannie suffered personally during this “thiefing expedition” when they stole her beloved horse: “They

took off a great many negroes and horses, among the latter was my beautiful gallant grey ‘Stonewall Jackson.’

He was a present from Pa.”

The Haskins house overlooked the Cumberland River. At dusk on May 12, 1863, Nannie wrote, “Those

hateful gun boats! They look like they are from the lower regions. Now this the second night that four of them have been anchored

in the river opposite our house. I know they are frightened, they have placed their gunboats so that if an attack is made,

they can shell the town. Poor cowards, I can just turn my head now and see them crawling about on the boats like so many snakes.”

About 1,500 Federal troops occupied the city from 1863 to 1865, though the military commander, Col.

S.D. Bruce, a Kentuckian, attempted to make occupation as painless as possible. Nevertheless, the sight of African-American

soldiers carrying weapons was particularly galling to Nannie and other white Clarksvillians, while Union soldiers arrested

preachers they suspected of supporting the Confederacy and demanded allegiance from worshipers. Merchants had to take loyalty

oaths to stay in business.

Despite the presence of so many soldiers, life under occupation was chaotic. Hundreds of ex-slaves

populated numerous contraband camps. Some African-American men joined the Union or hired themselves out for labor; the Haskins

family hired young black women to do the cooking and housework. White refugees arrived as well, and by December 1864, Clarksville

held about 3,000 refugees — men, women and children — fleeing Sherman’s March.

Violence in the form of robberies, kidnappings, beatings and murders was constant. “The whole

county is alive with robbers, every night we hear of a new robbery and perhaps a murder,” Nannie wrote. “Every

minute of the day we hear of something startling, which four years ago would have made us ‘shake in our shoes,’

now merely give them a passing thought. War has hardened us.”

Social activities provided a respite amid the violence and turmoil. Nannie’s diary is replete

with accounts of parties, concerts, picnics, tableaux and dances. She often named everyone in attendance, and making special

note of the attentions of young men. Nannie could also dabble in youthful indiscretions: she once attended a party where people

were dancing; upon returning home her mother reprimanded her severely for dancing while in mourning for her brother. And in

some ways, her diary illustrates a young woman much like those in more peaceful times: the night after her 18th birthday party,

where the guests feasted on pound cake, ice cream and strawberries, she ended her entry on a melancholy note, wondering where

she would be 18 years later, and if she would make a mark on the world. Nannie resented the

occupying Federal troops. She wrote, “Never see a Yankee but what I roll my eyes, grit my teeth, and almost shake my

fist at them, and then bit my lip involuntarily and turn away in disgust — God save us!” Not all the young women

felt the same way. Once after a concert at the Presbyterian church where Nannie performed, the event was marred, she noted,

by “some young ladies up in the gallery [who] carried on shamefully with the Yankees.” Even still, the Southerners

ended the evening’s orders with a round of “Dixie,” defying Union orders.

Throughout the war years the Haskins family desperately sought accurate information on the

war, news of the fate of soldiers they knew, and in particular of Ben Haskins, who was captured at Gettysburg. Nannie was

eager to believe good news for the Confederacy and disregard bad news as “yankee lies.” (Ben survived the war,

living until 1912.)

Finally, even Nannie could not deny that her short-lived nation was defeated. When

news that Richmond had fallen reached Clarksville, the Union troops celebrated, festivities that drove Nannie to profanation.

“These blue D—ls desecrated our churches by ringing the bells. They did all in their power to arrile

us … my heart sank within me.”

After the war Nannie married a widower, Henry Williams, who had four young children;

together they had six more. The sporadic entries in her diary continue until 1890, though Nannie never alluded to the war

again after its end. Nannie Haskins Williams died in 1930 and is buried in Clarksville’s Greenwood Cemetery.

Minoa Uffelman is an associate professor of history at Austin Peay State University

in Clarksville, Tenn., and an editor of the forthcoming diaries of Nannie Haskins.

Nannie Haskins Williams

(b: May 24, 1846 - d. July 13, 1930)

Clarksvillian Nannie Haskins kept a diary through much of her life. She was 16 when she began the Civil War portion of

the diary in 1863. The family lived in a home on the southwest corner of College and Second streets.

The daughter of E. B. Haskins and Tennessee Stark Williamson Haskins, Nannie had three brothers—Benjamin Aaron

Haskins, Robert J. Haskins and Tennessee Stark Haskins. Her father is listed as a physician in the 1850 census. Ben Haskins

was born in 1841 and served as a first lieutenant in Company A of the 14th Tennessee regiment of the Confederate army. He

lived until 1912. Robert was born in 1843 and joined Company A of the 49th Tennessee regiment. He was captured at Fort Donelson

and died in Chicago in 1864 or 1865 while a prisoner of war. Both brothers may be buried in Riverview Cemetery. Tennessee

Stark Haskins was younger than Nannie and may have died before reaching adulthood.

Nannie Haskins married Henry Williams in 1870.

They may have lived in Birmingham, Alabama, for a while and then in Todd County, Kentucky.

Williams had four children by a previous marriage, and he and Nannie had six children. Nannie and Henry and several of

their children are buried in Greenwood Cemetery.

Nannie Haskins’ Civil War Diary: Selected Entries from 1863

Monday Morning February 16th ‘63

Again I have commenced a journal. I used to keep one but two years ago when the war broke out, I ceased to write in it

just when I ought to have continued. Yes! Our country was then perfectly distracted; To arms! To arms! was echoed from every

side; volunteer companies were being gotten up all over the country to fly to her rescue; and of course Clarksville did her

part….[Haskins goes on in this first entry to describe the mustering of two Clarksville regiments, the fall of Fort

Donelson, Clarksville’s occupation, its brief reprieve from Woodward’s raid, and Col. S.D. Bruce’s recapture

of the city.]

Sunday evening, 22 February

This morning we were all awakened by the ringing of the church bells and the firing of the canon. At first we could not

conjecture what it was. Pa thought it was a fire. I was sure Morgan had come, but Ma suggested that it was Washington’s

birthday, and she was right. It is the twenty-second of February. This day one hundred and thirty-one years ago George Washington

was born the Father of this country and the Prince of rebels. He was the great leader of our forefathers who were his followers

when they rebelled against the tyrannical government of our mother country.

Thursday morning 16th-

It looks like spring is coming again—we have kept (?) an unpleasant winter—I do hope that spring with her

sunshine and blossoms will bring us peace to our country; this war has lasted so long—two years! It seems like two centuries.

Peace, peace, come to cheer us once again, and we will appreciate thy smile.

Friday, March 18-

The Yankees will have to pass through a “Longstreet,” level two “Hills” and climb a “Stonewall”

before they can get to Richmond—which is a pretty hard business for them to go about.

Sunday morning, April 26-

They have stolen all the provisions in the whole country, have pressed wagons and teams and negroes to work on the fortifications

(to shell our town when the confeds come) and thus they are trying to make every body take the oath even the women; “they

cannot support people who are not loyal.” But here is one who will not take an oath of any description.

May 12-

Those hateful gunboats! They look like they are from the lower regions. Now this is the second night that four of them

have been anchored in the river opposite our house; I know they are frightened; there they have placed their gunboats so that

if an attack is made they can shell the town, poor cowards. I can just turn my head now and see the men crawling about on

the boats like so many black snakes….

May 17-

[Diary notes Stonewall Jackson reported dead; Hill wounded.] …Our boys must have been in the fight—they are

in AP Hill’s division….I wonder whose heart is to be made sad by this latest battle—I hope that bad news

is not awaiting us.—sad, wanted to weep, mourn—But now my heart rebels; I feel as if I could fight myself. Never

see a Yankee but what I roll my eyes, grit my teeth, and almost shake my fist at him, and then bite my lip involuntarily and

turn away in disgust—God save us!

Saturday, May 30-

They have forced me to sign the parole of honor(?)—Oh how I do regret it—to morrow if I could do anything

against them I would do it; if I was sent to Camp Chase(?) the next moment—if they would have sent me to Evins (?) prison

I would have gladly gone instead of signing that thing—but they would have sent me South—There I would have no

where to go—no money to live on (for all that Pa has that he can possibly spare he sends to brother.) and I would be

an encumbrance to the South.

Sunday, July 12-

Night before last we heard that Brother Ben was well though a prisoner; he was taken at Gettysburg on the first day’s

fight, which was the first day of this month. Yesterday morning Mr. Bringhurst received a letter from his son Ed. who was

also taken prisoner and at the same time, he was then on parole in Baltimore, Md. There was eleven of privates of company

“H” taken and several from company “A.” They, the privates, are all on parole. This morning Mrs. Moore

received a letter from her son Lieut. Moore of Company “H,” stating that himself and Capt. Moore of the same company

were prisoners and confined at Fort McHenry, Baltimore; he said they were not exchanging officers at present and he did not

know how long they would remain there. We have heard nothing from brother except that he was a prisoner.

Sunday, July 19-

Last night we received the first letter from brother since he has been taken prisoner; he and the other officers have

been sent to Fort Delaware. General Archer is there. Brother says he is in need of clothing. Pa is trying to make some arrangement

to have his wants provided for. Last night George Faxon received a letter form Theo. Hartman, who was taken prisoner on the

third day’s fight—he gives a few casualties in the regiment: Willie McCullock was killed, he fell pierced through

the head by a minnie ball. Charley Mitchell was wounded. Bob Shackelford was wounded and taken prisoner. He said that Irvin

Beamont fell but he did not know whether he was wounded or killed. I hope it was not the latter. He spoke of several others

but I do not remember their names as I did not know them. I hope we will soon get all the particulars….

Monday, October 23-

[Haskins describes her living room with Pa reading, Nannie writing, Ma knitting, a lamp and her French books on the table,

noting how tranquil the scene would appear to a stranger, but]…“if he could look into our hearts (and some times

into my mothers eyes when all is quiet around her and she sits knitting in the corner) he would know that some thing has happened.

Once we were a gay and happy family—once there was six of us—now there is three left at home, two have been taken,

one is still battling for “freedom.” Oh God send him back to us, spare Ben (?) I pray! [She then goes on to wonder

whether she will ever marry and if she does will he be rich or poor, “a clodpole or a tadpole.” She breaks for

awhile and returns to the diary.] “At a later hour-I read what I wrote before I left Ma’s room and see how silly

I am. It is a blessed thing that no one will see this book but myself, for one moment I run on a sad strain; the next I dash

off on something about marrying. I am a simpleton any way and I am afraid I will never be any thing else.

Archival Housing of Diary

The Civil War diary, along with some letters to her daughters, is in the Tennessee State Archives. The papers were a

gift of Lucy Stark Williams and Rowena Day of Clarksville. Here is the library’s description of those papers:

(H)er diaries offer penetrating views of the effect of the war on a small community. The Nannie Haskins Papers may be

ranked with other female diarists of the Civil War era, in the detail and perception of her work. For the researcher, the

diaries provide a brilliant view of the war in the South.

The University of North Carolina purchased later portions of the diary in 1955. Here is the description of its holdings:

Williams, Nannie Haskins, b. 1846. Diary, 1869; 1871; 1880-1883; 1885-1890. 1 volume.

Intermittent diary of Nannie Haskins Williams, a woman living on a farm in Todd County, Ky., recording family concerns,

activities of her children and her hopes for them, everyday life and difficulties, Christmas festivities, thoughts and interests,

religious life, her reading, her secret efforts at writing a novel (a "romance of practical life"), and news of the county

and of adjacent Montgomery County, Tenn.

|