|

MARY L. PHILIPS was born on 1 May 1837 in Davidson Co TN. She died 19 Sep 1919and is buried at Philips Cemetery in the

Wharton Lot. She married JOHN FELIX DEMOVILLE on 21 Nov 1854. He was born about 1837.

Shortly before Mary L. Philips married John Felix Demoville in December of 1954, her

cousin, Martha M. Williams married Andrew Jackson "Jack" Duncan on 6 June 1854. The two purchased a house located downtown

at the corner of Spring and Vine Streets. Before long, they sold the house to Martha's cousin Mary and her husband

John Felix DeMoville and moved out Franklin Pike near Ft. Negley. The DeMovilles lived in the house at Spring

and Vine for a number of years. The following story describes what happened to the house and lot.

align="center">

The Street Where We Lived

Metro police officers had already blocked off the road between Third and Fourth Avenues. Through

a muddy haze of smoke, a fireman, hovering aloft in a cherry picker, was aiming a high-powered jet of water into the gutted

hulk of a three-story building just off Sixth Avenue. As still more fire fighters scrambled across a nearby roof, the smoldering

rubble sent up plumes of smoke. Across the street, alongside McKendree Methodist

Church, a small crowd had assembled in a parking lot, once the site of the Tennessee Theater and its skyscraping 12-story

tower, the Sudekum Building. In the 1950s, the theater had gleamed with brass murals, aluminum fixtures and slabs of polished

marble. On this cold January night, not a clue of its existence remained. In the place where it had stood, a few people—reporters,

pedestrians, tourists on their way back from a night on Second Avenue—had gathered to watch Church Street burn. Earlier in the day, the street had been doing better business than on most recent Saturdays. But it had not

really been crowded—not mobbed the way it was in the old days, when Church Street was the pulsing heart of the city,

its sidewalks thronged with afternoon shoppers. Even that morning’s rush had had a sense of foreboding. On that Saturday,

just as it had done for 90 years, the Castner Knott store at 618 Church opened its doors for business. After the doors closed

that day at 6 p.m., they would never open again. By 1 p.m. the store had been

very nearly picked clean. A pathway led through a maze of empty display cases. A few rumpled dress shirts lay piled on long

tables. Men hurriedly rifled through racks of marked-down suits, while women loaded up on pantyhose. The bargains were impressive—an

Oxford shirt for $15, a sweatsuit slashed to half-price—but the mood was less than festive. Asked if she would miss the store, a woman thumbing through packs of hosiery said, “No. There’s

a Castner’s five minutes from my house.” She shrugged. “It’s not nice to say, but it’s true.”

John Felix DeMoville The Demoville Home

Mary L. Philips

The above plaque was displayed in the Caster-Knott Department Store to remember the home

that previously stood on that site.

A woman in a red coat led a little girl upstairs toward the children’s department. Without pausing, they walked

past a bronze plaque on the wall beside the staircase. “This tablet,” the worn plaque

proclaimed, “is set at the site of the Felix DeMoville residence, famous for 45 years as the

home of a refined, cultivated and hospitable family, wherein good cheer, gentle manners and intellectual intercourse brought

cordial charm to gracious entertainment.” The DeMoville house had stood there,

the plaque explained, from 1857 to 1902. Next to the plaque, a red construction-paper sign was taped to the wall.

The sign read, “Final Week.” In 1862, while Union forces occupied Nashville, setting up a makeshift hospital

at McKendree Methodist Church, Yankees and Rebels uneasily shared Church Street, then known as Spring Street. In Nashville

the Occupied City, Walter T. Durham paints a picture of Nashville women, the residents of Spring Street’s elegant

homes, greeting Yankee officers with open contempt and hostility. The daughter of the proprietor of the old St. Cloud Hotel

at Fifth and Church was dragged before Gov. Andrew Johnson for spitting on passing Yankees from the hotel’s balcony. Spring

Street was intersected by Cherry Street (now Fourth Avenue), which, by the end of the century, was thick with rowdy saloons

and disreputable houses. Cherry Street’s reputation was so foul, according to historian William Waller, that women had

to enter the famed Maxwell House Hotel from a special entrance on Spring. If a woman set foot on Cherry Street, her reputation

was destroyed. Before it gave way to saloons and dens of iniquity, the so-called “men’s district” on Cherry

had boasted fine haberdasheries and tailor shops. Now it drew an adventurous mixture of the upper and lower classes: middle-class

gentlemen dashed off to saloonkeeper Sid Lucas’ Southern Turf for a game of chance, and riverboat roughnecks ambled

up from the Cumberland. Brazen prostitutes from the “demimonde” near Capitol Hill paraded down to Spring Street’s

shops in carriages. A city ordinance forbade them to walk the streets. By the turn of the century, proper Nashvillians

would have been equally disturbed by the rash of theaters that had sprung up along Spring. The finest of these was the Vendome

at 615 Spring, which opened in October 1887. With its spacious box seating, the Vendome was modeled on the fine opera houses

in other cities. Its owners capitalized on Nashville’s access to railroads, which brought in the touring companies and

performers that crisscrossed the continent. During its first two decades, the Vendome hosted some of the brightest lights

of the interntional theater, including Lillie Langtry, Lillian Russell, the legendary Shakespearean actor Sir Henry Irving,

and Ethel Barrymore, along with personalities such as boxer John L. Sullivan and poet James Whitcomb Riley. As soon

as it opened, however, the Vendome clashed with McKendree Methodist Church down the street. According to a remembrance by

Thomas H. Malone in William Waller’s Nashville During the 1890’s, the theater’s gala opening, a

performance by prima donna Emma Abbott and her English Grand Opera Company, was scheduled for the same night as a meeting

of the church’s Board of Stewards. The starry-eyed stewards, straightaway, had abandoned God’s work for a night

at the opera. On the following Sunday morning, McKendree’s minister, the Rev. Warren A. Candler, was livid. He

smote his congregation with the sort of wrath that led Malone to liken him to “a particularly venomous stumpy-tailed

rattlesnake.” After Candler’s 40-minute tirade on the evils of the theater, a woman’s voice rose unexpectedly

from the congregation. “I, Emma Abbott,” said the woman, rising majestically to her feet, “wish to denounce

as false and un-Christian what has just been said.” Rev. Candler sputtered with rage as the diva delivered an extemporaneous

defense of her profession and swept from the church with a grand flourish. Opinions vary as to whether it was she or Candler

who had earned the applause that ensued. By 1900, the eight-block stretch leading up Spring Street from the river was

a microcosm. Mercantile enterprises and mills nestled near the bustling waterfront on Front Street (now First Avenue). At

the Diehl & Lord beer-bottling plant, working men could stop for a quick pint of Belfast ginger ale before heading up

Spring, toward the excitement uptown. At the eastern end of Spring Street, competing newspapers had set up their offices:

The Banner stood at the corner of Printer’s Alley; the American was housed at Cherry and Spring. A

Baptist church had once stood at the corner of College Street (Third Avenue) and Spring. In the 1830s, however, Alexander

Campbell, a leader of the congregation, had denounced the Baptist denomination, forcing the church’s other members to

choose sides. The Baptists were driven from the church, and, in essence, the Church of Christ was born. Crossing Cherry

Street at the turn of the century, pedestrians had to watch out for the electric streetcars that had been installed in 1889.

The year before, in 1888, granite paving blocks had been laid by hand to prevent heavy horse-drawn wagons from sinking up

to their axles in muddy weather. Across the street from First Presbyterian Church (which, as Downtown Presbyterian Church,

is the oldest surviving building on Church Street) stood the new Masonic Lodge, where the young keyboard virtuoso Jan Paderewski

caused a sensation in 1896. At the corner of High Street (now Sixth Avenue), large red bins of sugar and coffee marked the

A&P. The smells of roasting coffee and baking bread wafted from William C. Collier’s famed grocery on the

ground floor of the Watkins Institute Building at 601 Spring. Upstairs, the Institute’s auditorium featured prominent

lecturers, while college students and well-to-do bachelors kept living quarters in apartments facing Spring. Watkins had become

a social magnet for the young couples who lived in the residential areas nearby. It was there in 1888 that a bright, energetic

entrepreneur named Herman Justi (later of the Nashville Trust Company) founded the literary society known as the Old Oak Club.

In Justi’s sumptuously furnished corner suite, the club’s members—who included newspaper editors, foundry

superintendents, lawyers, and professors from Vanderbilt and the University of Nashville—gathered to engage in discussions

and listen to papers such as “The Race Question in America.” In the midst of the urban bustle, nearby residential

neighborhoods provided Spring Street with its customers. In the 1890s, High Street, north from Spring, was one of the city’s

most desirable residential areas. It was lined with the stately homes of businessmen and politicians living near Capitol Hill.

Billy club-swinging policemen, dressed in knee-length blue coats with brass buttons, patrolled the neighborhood on foot. Just across from the old Watkins Building, where Capitol Boulevard is today, stood the old John Hill Eakin

home. Beside it, at the corner of Spring and Vine Street (now Seventh Avenue), stood the home of John Felix DeMoville, whose

family’s famous drugstore at 200 Cherry St. had supplied the city with pharmaceuticals and fine cigars since 1859. DeMoville’s

kept eight employees on hand constantly and boasted a soda fount carved of onyx. Throughout the 1890s, the DeMoville home

remained a center for Sunday-afternoon social gatherings. As a retail center Spring Street was the place

where a variety of classes, cultures, and competing interests collided. At the western end of Spring Street, where 15th Avenue

North runs today, stood the stone wall of the state penitentiary, separated from the downtown district by the railroad depot

and viaduct. Few businesses extended beyond the campus of the Nashville Female Academy at Spring and McLemore (now Ninth Avenue),

and even that area was considered part of the “suburbs.” For most of the 19th century, the center of Nashville

business had been the Public Square in front of the Courthouse. There Nashvillians shopped for everything from groceries to

fabrics, but the steep hill that descended from the Courthouse to Broad encouraged merchants to develop businesses along the

city’s more level streets, which ran from east to west. By the turn of the century, the flow of business began to move

inexorably westward, heading toward the residential areas near Spring Street. Clustered along Summer Street (now Fifth Avenue)

were Nashville’s retail establishments, primarily specialty stores, including Thompson & Kelly (sellers of fine

crystal and silver), the Branham & Hall shoe company, and one of the most famous stores in Nashville at the time, Lebeck

Bros. In the early 1900s, two upstart firms refired the competition among Nashville’s already competitive retailers.

In 1903, three friends, Paul L. Sloan, John E. Cain and Cain’s brother Patrick, went together to purchase Kalmbach’s

Beehive, a thriving little store at 233 North Summer St., just across from the entrance to the newly opened Nashville Arcade.

The three partners renamed the store Cain & Sloan Co. and bombarded the local public with ads promising “great values

in Gloves, Hosiery, Underwear, Corsets, Leather and Fancy Goods.” The chief rival of Cain and the Sloan brothers

was a dry-goods operation housed in a six-story building just a few doors down the block. In 1898, while the country at large

was immersed in the Spanish-American War and the city was still beaming from the festivities of the Tennessee Centennial,

Nashvillians Charles Castner and William Knott had opened the Castner Knott Dry Goods Co. at 207-209 North Summer St. Nashville’s

first department store, Connell, Hall and McLester, had opened earlier that year, near St. Cloud Corner at Summer and Church,

but Nashvillians weren’t used to the concept of one-stop shopping, and the store had quickly gone bankrupt. Where

Connell, Hall and McLester had failed, though, Castner and Knott thrived. By 1903, William Knott had even done the unthinkable:

He had opened his very own buying office in New York, allowing the store to purchase fashionable goods cheaply, and directly,

in the world’s retail center. In 1973 93-year-old Agnes Nance, by then the store’s oldest retired employee, recalled

being dispatched to New York on a buying trip in 1905. Nance told The Tennessean that her father, “an old Confederate

soldier,” had promised her that he could be in New York at a moment’s notice if she received any lip from the

Yankees. By 1906, in an attempt to create less confusion for tourists, Nashville’s downtown streets had been renamed,

and Spring Street had been rechristened Church Street, in recognition of its many houses of worship. Meanwhile, the Castner

Knott operation had outgrown its six-story offices, leading the store’s owners to take a calculated risk.

In 1902, the DeMoville home had become vacant, making available an expanse of property at the corner of Church and Seventh

Avenue. Despite their fears of moving into what was virtually a residential area, Castner and Knott forged ahead. In 1906

they moved two blocks up Church Street, opening the doors of a massive emporium that offered everything from wood-burning

stoves to a fully stocked basement grocery. The retail explosion on Church was under way. As soon as Castner

Knott vacated its space at the corner of Fifth and Church, Cain & Sloan shortened its name to Cain-Sloan and took over

the building, adding a carpet department and a full-service ladies’ department to compete. Fifth Avenue became the province

of huge five-and-dime stores: McClellan’s, Woolworth’s, W.T. Grant and Montgomery Ward all operated within a two-block

stretch. By 1913, the huge retail establishments had transformed the street. In the 600 block of Church Street, shoeshine

parlors and fruit vendors jostled alongside some of the city’s best-known businesses: Joy’s Flowers, which had

recently moved into the Watkins Building; H.G. Hill’s grocery; Joseph Morse & Co., one of Nashville’s most

respected men’s clothiers; and the newly relocated Mills Bookstore. The original Mills store had been opened in 1892

among the Fourth Avenue gin mills. Its 18-year-old entrepreneur, Reuben M. Mills, claimed he had read only three books in

his life before he opened his store. If shoppers grew bored or tired, they could duck into one of the many theaters

that had opened downtown to accommodate the nation’s newest craze: motion pictures. In 1907, two young German-American

brothers, Tony and Harry Sudekum, bankrolled by capital from Nashville’s large German business community, opened the

Dixie Theater, an early nickelodeon on Fifth Avenue. By 1917, Tony Sudekum owned three Church Street movie houses—the

Capitol, the Princess, and the Knickerbocker, which, in 1928, would make local history by screening the city’s first

talking picture, When Man Loves, a potboiler starring John Barrymore and Dolores Costello. Business was booming

on Church Street. The Depression would slow it down, but it would not bring it to a halt. In 1929, Tony Sudekum, already

one of Nashville’s leading businessmen, was forced to halt construction of his pet project, an Art Deco skyscraper to

be built at the corner Fifth and Church, on a lot belonging to the Odd Fellows fraternal organization. The slowdown was only

temporary. The Sudekum Building was finished in 1932. Nevertheless, the Depression did claim one major casualty on Church

Street. After decades of operation, Lebeck Brothers Department Store was forced to close its doors. In the bankruptcy

settlement, a long-term lease on the huge Lebeck building was awarded to Commerce Union Bank, whose president, Ed Potter Jr.,

didn’t want to see Church Street’s fortunes continue to decline. In 1942, according to Donald Doyle’s Nashville

Since the 1920s, Potter met a flamboyant retailer named Fred Harvey. Harvey, a veteran of Chicago’s bare-knuckled

retail wars, dreamed of opening his own department store. Potter agreed to set him up in the old Lebeck Bros. building and

provided him with a substantial line of credit. To give Harvey immediate credibility, Potter set the retailer’s family

up in a house on tony Belle Meade Blvd. The hedges were trimmed low so that passersby could be sure to see the Harvey name

painted on the mailbox. Fred Harvey’s department store was like nothing Nashville had ever seen. Castner’s

and Cain-Sloan were relatively sedate, but Harvey’s was like a circus, complete with cages of chattering monkeys, mynah

birds and the store’s trademark carousel horses, which Harvey purchased from the old Glendale Park carnival off Franklin

Road. Cain-Sloan prided itself for elegant reserve—it had special machines and dishes of talcum that allowed ladies

to try on gloves without handling them. Harvey’s, by contrast, had the first escalators. Harvey’s also accepted

returns where other stores might have refused, and it offered credit to customers with modest income. Harvey had revolutionized

Nashville retailing. He had also found bitter enemies in the Cains and the Sloans. “Cain-Sloan represented the

old Nashville—the steeplechases, the bluebloods,” recalls Fred Harvey Jr., who succeeded his father as president

of the company and worked there for 35 years. “My father was a showman. He couldn’t believe it when he came to

Nashville. He shook up the establishment pretty good.” Indeed. Bolstered by an innovative and unrelenting “Harvey’s

Has It!” ad campaign, the new store was amassing annual sales of $500,000 by 1946. By 1950, income had risen to $9 million.

In 1954 the store posted annual revenues of more than $11 million—surpassing Cain-Sloan for the first time. On

Feb. 28, 1952, as searchlights swept the night sky, limousines rolled down Church Street for the gala opening of the Tennessee

Theater, a massive 2,000-seat auditorium adjoining the Sudekum Building. For its opening night, which commanded ticket prices

ranging from $10 to $50, the Tennessee booked a Technicolor musical called About Face. As the movie’s stars

Gordon MacRae, Phyllis Kirk, Lex Barker, Joe E. Brown and Nashville native Claude Jarman Jr. entered through the marble lobby,

Tennessee’s three presidents, in bronze bas-relief, gazed down from the wall. A brass ornamented mural depicted the

filmmaking process from typewriter to screen. Tony Sudekum, however, could not be on hand. He had died in 1946 before seeing

the theater completed. The day after his death, City Hall was closed in his memory, as was every movie house in town—except

the one he didn’t own. When longtime Nashvillians talk about the glamour and excitement of Church Street, these

are the days they remember—the period from the 1940s through the ’50s, when women still wore white gloves to shop

at Tinsley’s, when buses carried teenagers from Belle Meade and Green Hills downtown for a movie at the Knickerbocker

and a sack of 6-cent hamburgers from the Krystal Grill. Nashville native Lacey Perry recalls visiting Castner Knott when it

still had not only an upstairs phonograph department but provided listening booths where the records could be auditioned.

The corner listening booth was the most popular, Perry remembers, because its window overlooked Church Street’s most

popular hangout, the Candyland at 631 Church. Candyland made its own ice cream in the basement, and on Saturdays it

would fill with rambunctious teens. “That’s where I smoked my first cigarette,” Perry recalls fondly, “an

Old Gold.” At Easter, girls would purchase baby ducks and head down to Cross Keys for a 15-cent grilled cheese sandwich

and a 10-cent Coke; older boys might drop by Corsini’s restaurant on Seventh, which reportedly started serving Nashville’s

first pizzas to satisfy the demand of soldiers returning from Italy. To experienced travelers, jaded by visits to New

York and Europe, Church Street may have seemed hopelessly provincial. To people who grew up in the outlying counties, where

the lure of a city, any city, promised adventure, it sparkled. Church Street, however, does not hold sweet memories

for everyone. Segregation was a bitter indignity for black Nashvillians, who poured money into Church Street’s retail

establishments but were not allowed to eat at its restricted lunch counters. In 1900, during the Vendome’s heyday, a

troupe of black entertainers led by classically trained soprano Madame Sisieretta Jones may have performed onstage, but black

patrons were still consigned to the balcony. In 1950, black shoppers may have spent thousands of dollars at Cain-Sloan every

year, but they were refused service at its fourth-floor Iris Room restaurant. By 1958, the advances of the civil rights

movement convinced black Nashvillians that it was time to act. That year, the Nashville Christian Leadership Conference (NCLC),

a branch of Rev. Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), organized under the leadership

of the Rev. Kelly Miller Smith, minister of Nashville’s black First Baptist Church Capitol Hill. Smith met with local

students to devise a nonviolent response that would chip away at the city’s long-standing segregation policies. The

target was the downtown retail district, where black shoppers were still treated as second-class citizens. One exception

was Mills Bookstore, whose manager, Bernie Schweid, remained a staunch opponent of segregation. “I think the fact that

he was from the North made it easier for him to accept integration,” remembers his widow, Adele Mills Schweid, whose

father, Reuben Mills, owned the store until the early ’60s. “[Bernie] didn’t have to struggle to overcome

prejudice.” The store’s regular clientele included students from TSU and Fisk University, and it employed one

of the first black cashiers on Church Street, a former maid named Annie Huey. “There were probably some [other

merchants on Church Street] who thought segregation was wrong,” Adele Schweid observes. “Most people were resigned

to integration as inevitable. My father had been a typical Southern gentleman, and he came to realize how horrible segregation

was.” Sit-ins were staged at the Cain-Sloan and Harvey’s lunch counters in 1959. Black students would make

purchases at the stores and then sit at the whites-only lunch counters. Inevitably, they would be refused service. When they

refused to leave, the counters would be closed. As the protests continued into 1960, tensions intensified. On Feb. 27, in

a strictly nonviolent protest, black students sat down at the Cain-Sloan lunch counter while the threats of white onlookers

rained about them. On Fifth Avenue, at McClellan’s, angry whites yanked a protester, Paul LaPrad, from his seat and

beat him while onlookers did nothing. By March 2, the sit-in campaign extended to Harvey’s lunch counter. When a crew

filming a CBS White Paper arrived later in the month, the only Church Street merchant who would admit them to his

store was Bernie Schweid. Business was bad, he told them. The blacks stayed away in protest, and the whites stayed away in

fear. That left the green people, Schweid said, and they didn’t buy much. Eventually, an Easter boycott of downtown

forced merchants to make a choice between integration and eventual bankruptcy. Behind the scenes, the unlikely team of Harvey’s

treasurer Greenfield Pitts and Cain-Sloan president John Sloan approached other merchants about the possibility of a quiet

desegregation of the lunch counters. On May 10, 1960, Harvey’s, Cain-Sloan and four other stores permitted blacks to

eat at their downtown lunch counters. The struggle for desegregation continued well into the decade, but by 1970, Church Street

belonged to everyone. The sad truth, though, is that by then it was too late. The death knell had begun to ring for

Church Street in 1955. That year saw the opening of Green Hills Mall, the first shopping center to carry major retail establishments

into Nashville’s outlying areas. With the opening of 100 Oaks in 1967 and Harding Mall in 1968, shoppers no longer had

to come downtown to find Castner’s, Harvey’s, or Cain-Sloan; the stores had come to them. In the mid-1970s,

when Hickory Hollow and Rivergate Malls opened and as the Grand Ole Opry abandoned downtown, the retail giants were dealt

a crippling blow. Not even Mayor Richard Fulton’s controversial Church Street redevelopment in the late ’70s could

stanch the flow of business from the area. By that time, noise, pollution and congestion had driven most residents away from

downtown, eliminating the need for the small service stores, restaurants and groceries that had given Church Street its character

for more than a century. “No one had the foresight to see that the cities were dying,” explains Adele Schweid.

Fred Harvey Jr. agrees: “What’s happening downtown is certainly not unique,” he says. “You can go

to any city that isn’t New York or L.A. and see the same thing. The only reason to go downtown now is if you work there—and

if you work there, you aren’t shopping.” Levy’s, Nashville’s oldest family-owned clothing store,

maintained a downtown location for 125 years before closing its Sixth Avenue store in 1980. “People don’t make

a game out of shopping the way they used to,” says A.J. Levy, who now heads the family business. “Back then, women

went to town in white gloves and spent the day shopping. Today, people just want to get in and get out.” In 1984,

after 42 years, Harvey’s closed its downtown store. The building stands empty near the corner of Fifth and Church. Cain-Sloan

followed suit in 1987; two years ago the Cain-Sloan was demolished and replaced by a parking lot. The Tennessee Theater and

Sudekum Building, despite their historic status as two of the few remaining Art Deco structures in the country, collapsed

in a heap of rubble in 1990, destroyed to make room for developer Tony Giarratana’s plans for an office building that

never materialized. They were replaced by still more parking lots. Signs of life still flicker in Church Street’s

retail district—the Petway-Reavis clothing store remains, and the embattled Church Street Centre mall attempts to recall

downtown’s retail heyday. Meanwhile, Watkins Institute has announced plans for a multimillion-dollar expansion. For

the first time in nine decades, though, the Castner Knott storefront stands empty, with little hope for revival. Like the

buildings in the adjacent 700 block—especially the fine 12-story Bennie Dillon Building, whose sagging ceiling tiles

dangle like rotting teeth—it stands lifeless, final as a tombstone. One week after the fire that gutted 602 Church

Street, a sudden snowstorm blanketed the entire city. It covered the sidewalk outside Castner Knott and piled into drifts

at the corner where the Maxwell House Hotel once stood. It covered the parking lots where theaters and dreamlike department

stores once stood. It covered the rubble of still other vanishing buildings, it piled up against still other boarded storefronts.

The streets were desolate, and the driven snow turned people and buildings alike into pale ghosts. For the first time

in a century, Church Street was utterly quiet.

John Felix DeMoville was in the drug business with William Wells Berry.

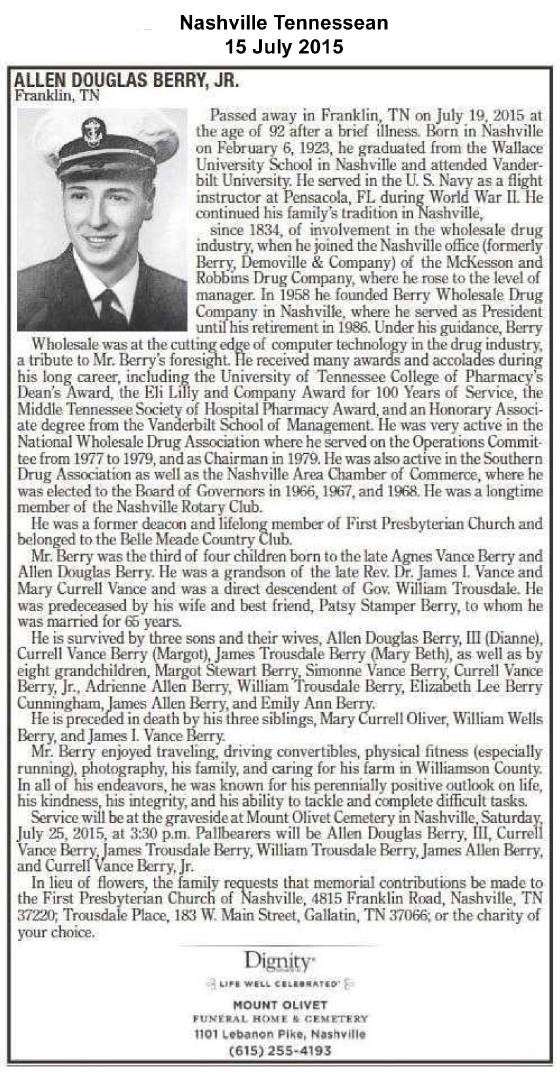

The above obituary tells the story of Allen Douglas Berry Jr. who is a grandson of this William Wells Berry Sr who

died almost 100 years ago. He continued in the family business.

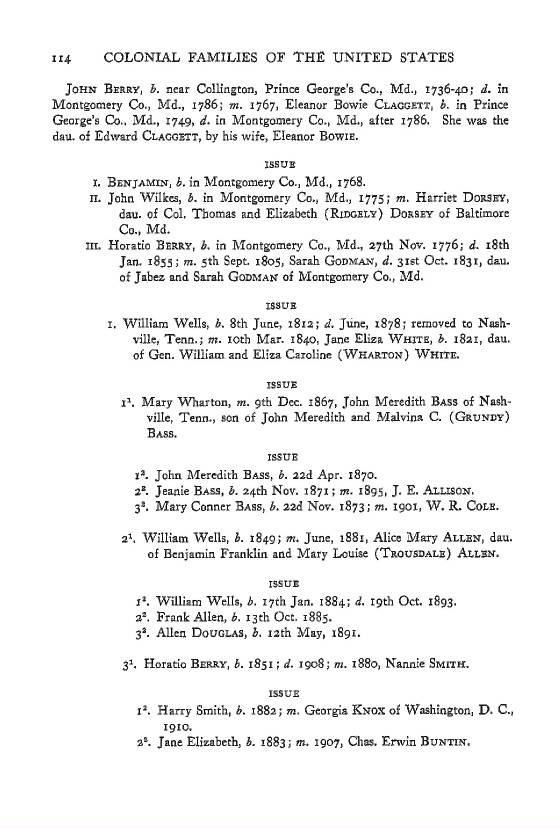

As the page from Colonial Families of the U.S. below describes, Allen's grandfather William Wells Berry is

a brother of Horatio Berry whos son is Col. Harry S. Berry, the namesake for Berry Field in Nashville.

Named in honor

of Colonel Harry S. Berry, state administrator of the WPA, Berry Field consisted of a terminal

building, two hangars, a 4,000-foot concrete runway and a flashing beacon. The three letter identifier,

BNA, stands for Berry Field Nashville. American and Eastern airlines were

the first air carriers to serve Nashville, and within

the year, 189,000 passengers had used the

facilities.

|

|